Having completed a series of posts covering an historical sociological framework for PSA - Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 - it now seems appropriate to provide a modern financial perspective in support of the model. Though prior posts have applied the PSA model to higher education (HE) finances in the American and Chinese systems, it is important to offer a more nuanced financial picture. To this end, I offer a two-part series in which HE financial data from Canada and Australia is used to demonstrate the viability and desirability of PSA. Followed by Australia, this post looks at Canada.

On February 8th of this year, Alex Usher, President of Higher Education Strategy Associates (HESA), presented what he called, “A New Way of Looking at Institutional Revenues.” A standard way of analyzing higher education institution (HEI) finances is to calculate the revenue per full-time equivalent (FTE) student. It is a simple calculation that divides various revenue sources – public funding, tuition, sales, investment, etc. – by the number of FTE students. For instance, if system-wide revenue is $100 billion and there are 2 million FTE students, then the figure is $50,000 per FTE student. Since without students there is no HE industry, we might say this represents the HEI revenue made possible by students.

Usher’s perspective suggests the same sort of calculation

but with a different and equally necessary denominator – academics (faculty,

teachers, lecturers, professors). This is worth consideration, since together these

are the only essential denominators in any education system – teacher and

student. The rest is mere means - including universities and colleges.

From its inception, this has been the perspective of PSA. It

is the obvious choice of denominator if the aim is to develop a model that

converts academics from HEI employees to independent professionals in private

solo or partnership practice – as physicians, psychiatrists, architects,

lawyers, dentists and other professionals offer their equally valued services.

This is a model where HEIs are exposed as cost-intensive, unnecessary middlemen,

as mere facilitators of the HE services academics offer students and society.

I don’t need an HEI employer in order to provide my expertise

to the public - and I am not alone. PSA maintains that all fields of study (FOS)

can be at least partially and in most cases completely converted to the professional

service model. Not only is the conversion viable, it is desirable, offering numerous

benefits across metrics such as: access, equality, quality, compensation, cost,

and stability.

As we venture into the financial basis for this claim, it is

important to note that there is considerable variation in the quantity and

quality of data for HE systems around the world. Some of the variance is

shameful, some of it understandable. Mixed data profiles mean that the

financial analysis for each country does not readily include the same kinds of information

and measures – though effort has been made to standardize. Throughout the

series distinctions in data profiles are made clear, particularly when data

speculation or cross-country analysis are offered. For each country, the

analysis is broken down into several broad categories: i) tuition; ii) student aid;

iii) HEI revenue; iv) HEI expenditure; v) and government expenditure. The

financial data in each of these categories is analyzed in several ways using an

academic denominator and an academic practice expense profile unique to each

country. The aim is to demonstrate that professional private academic practice is

desirable competition or compliment for the HEI model of universities and

colleges which we have inherited.

Canada

- Professional Private Academic Practice

To begin, we turn to my birthplace, Canada, where the

available data offers a clearer picture of universities than of colleges. The national

office, Statistics Canada, collects incomplete and inconsistent data on college

academic labour or tuition and fees. Further, even within the university system,

data on full- and part-time contract academic labour is partial and sporadic.

Consequently, analysis is restricted to universities and the use of a postulated

academic staff denominator.

Methodology

Across this series several key data points are collected,

including: tuition & fees; student aid; student enrolment; teaching staff; teacher-to-student

ratio; HEI revenue; HEI expenditure; and government expenditure. However, it is

important to offer an account of the data wrangling and wringing used to zero

in on the relevant figures as they pertain to universities.

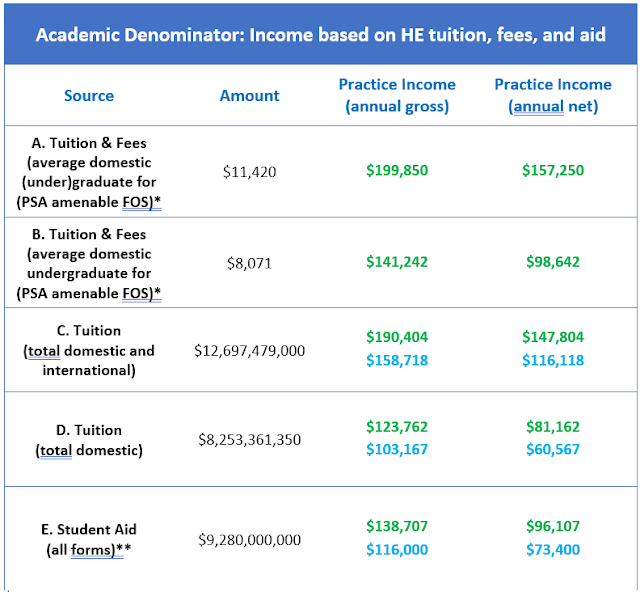

First, the all-important FTE academic denominator of 66,687 is arrived at using data from Stats Can and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA). The Stats Can data point is 47,007 full-time university teaching staff, including: full, associate, and assistant professors, along with all those below the rank of assistant professor, including lecturers, instructors and other teaching staff.[1] Based on data culled from Stats Can and the Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT), the 2018 CCPA report, “Contract U: Contract Faculty Appointments at Canadian Universities,” claims 59% of teaching staff are full-time.[2] Using these two data points, a total headcount of roughly 80,000 teaching staff is extrapolated, along with a part-time teaching staff headcount of 32,800, which is converted to an FTE of 19,680 using a 0.6 multiplier. Combining the 47,007 full-time and 19,680 FTE part-time figures we get an FTE academic denominator of 66,687.

With a 2019-20 FTE student university enrolment of 1,162,052, this gives us an FTE teacher-to-student ratio of 1:17.5.[3] This figure includes international students who in 2019 totaled 235,422, all of whom because of visa restrictions it is assumed study full time.[4]

Second, two instances of data disaggregation were required.

The first is total tuition and fees for universities broken into domestic and

international figures (Table 1 below, Sources C and D). This was done using the oft

cited distribution of 35% as the percentage of fees contributed to HEI coffers

by international students. So, of the tuition and fees collected by HEIs, 65% comes from domestic students.[5] The second is total student aid (Table 1

Source E) broken into a university and college distribution of 58% and 42%,

respectively.[6] This aid includes all forms: loans, grants, tax credits,

CESGs, and institutional scholarships.

Third, there needs to be a number that represents the major

expenses of operating a professional private academic practice. To arrive at

this figure, a hypothetical practice was located in downtown Toronto, Canada,

with support staff and facilities that include: i) graduate teaching or

research assistance and ii) office and face-to-face classroom spaces.

i)

$33,000/year (GTA/GRA for 15 hours/week, 44 weeks/year,

at $50CND/hour) [7]

ii)

$9,600/year (private dedicated office and media-supported

classrooms) [8]

The result is an annual practice operational

expense of $42,600.

Finally, it must be noted that some of the data used in

Tables 1 and 2 – including tuition & fees; revenue; and expenditure - is sourced

from Statistics Canada which describes its coverage as “all degree-granting

universities and colleges.” This is not ideal since every attempt has

been made to restrict analysis to universities alone. However, based on the

list of degree-granting university and college members and non-members of the

Canadian Association of University Business Officers (CAUBO), this discrepancy

is negligible for the present purposes. With only a few small sized

institutions as exceptions, the CAUBO list from which the Stats Can data is

composed, includes all the major HEIs in Canada and so within this scope of

discrepancy, the data is considered representative of the university

circumstance.[9]

The result is two tables of calculations that use various existing financial sources as revenue for the operation of a hypothetical professional private academic practice, as envisioned by PSA. Since these calculations use an academic denominator, the revenue is referred to as income for an academic in solo practice.

*PSA amenable FOS include: Executive MBA; Regular MBA;

Business, management and public administration; Mathematics, computer and

information sciences; Education; Architecture; Law; Social and behavioural

sciences, and legal studies; Visual and performing arts, and communications

technology; and Humanities.

**All student aid (E) includes: loans, grants, tax credits,

CESGs, and institutional scholarships.

Discussion

In closing out his HESA blog post suggesting the use of an academic

denominator, Alex Usher says, “Figure 5 [shown below] probably explains a great

deal about the differences in faculty salaries across the country. Basically,

if you maximize both international student numbers and the use of sessionals,

faculty can find themselves pretty well-off.”

As Usher intimates, the rosy picture for full-time tenured

and tenure-track faculty depends on vulnerable international student revenue

streams and potentially exploitive labour practices – both of which embody dangerous

slippery slopes of an economic and ethical variety. But unlike the HEI model, PSA

can avoid these conditions.

Using an FTE teacher-to-student ratio of 17.5 and an average

(under)graduate tuition and fee of $11,420 for FOS which are readily converted

to the PSA service model, we find academics stand to earn a net of

$157,250/annum - were this money paid directly to academics who offer their

services in professional society and practice, rather than to the universities

and colleges that employ them under the HEI model (see Table 1 Source A).[13]

If the calculation is restricted to undergraduate FOS readily amenable to PSA,

then the net income for professional academics is $98,642/annum (see Table 1

Source B). The income range is a consequence of the former containing graduate FOS

with relatively high tuition such as Executive MBA ($56,326) and Regular MBA ($27,397).[14]

Excluding those with senior administrative responsibilities

and faculty of medicine and dentistry, the first of these PSA incomes is consistent

with the 2019 national average of $160,183 gross/annum for full professors.[15]

When full, associate and assistant professors are combined with lecturers the

national average gross income for full-time teaching staff at

universities is $120,492, nearly $13,000 less than the net for all

PSA academics.[16] That is, based on these calculations, the net income of

$157,250 is not an average for PSA academics, but rather the income that every

single FTE academic can earn, all 66,687 of them. It is important to further

underscore how impressive is this calculation, for as the teacher-to-student

ratio of 17.5 includes international students, the $11,420 figure with which it

is multiplied is based only on the average tuition and fee for domestic

students (Table 1 Source A). In 2019-20, international students numbered

235,422 and spent on average $29,714 for undergraduate and $33,703 for graduate

FOS.[17]

As a response to funding problems, whether in-country or

through satellite campuses in foreign countries, the increased reliance on

international student tuition leaves HE systems vulnerable. As Usher notes,

“the $4.11 billion increase in international student tuition fees since 2012-13

is slightly higher than the $4.09 billion increase in operating expenditures

over the same period. Thus, 100% of all increased spending over the past seven

years has come from international student fees.”[18]

Higher education is a pillar of society that must not risk compromise

by a model that desperately operates on revenue sources susceptible to serious

and routine disruption from global economic recessions and pandemics or changes

in government policy, to name but a few of the disruptive and corruptive

forces. For instance, there is little security in Duke, NYU, and UC-Berkeley bolstering

their bottom-lines by opening foreign branch campuses or dual-degree programmes

in China, where in 2021 the State Council government almost overnight shut down

the country’s entire private education tutoring industry – a long-established

industry that by 2016 was worth $100 billion USD.[19] As anyone with business

aspirations in China knows, all such ventures are fraught with risk, but especially

foreign ventures.

Aside from economic risks to the stability of HE, consider

the risk to professional ethics of an HEI model that must admit ever greater

numbers of international students from countries such as India and China, whose

L1 is not English, who come from education systems with different standards, different

methods of teaching and evaluation, different classroom cultures, and who expect

a diploma in return for their substantial investment of tuition. In these

conditions: Can HEIs afford to turn down applicants who have the financial, if

not scholastic, means to complete a degree? What admission requirements will be

used? What evaluation standards at the programme and course levels will be used?

Can part-time faculty risk their precarious employment by failing too many international

students? How diligently will cases of gaming the system be investigated and prosecuted?

These, and other, suggestive questions deserve greater

treatment than is appropriate here. But on a personal level, I will say that after

having taught in the Canadian system for over 10 years, I am now on my fourth

year in China’s HE system at institutions where students pay full price (i.e.,

no government subsidy) and my superiors have routinely asked me to lower the

failure rate in my courses, while my employment contract stipulates that I can

fail no more than 10%. Each time I have refused to do so, knowing perfectly well

it might mean non-renewal of my contract - to mention the least of harms an employer

can inflict on someone with the precarious employment status of a work visa.

In countries where the HEI model persists in its reliance on

employment precarity and international student revenue, what effect does this

have on the quality of HE – or the professional and personal integrity of

academics and students? Or the integrity of HEIs for that matter, as the case

of my PhD alma mater evinces, having been found guilty of essentially selling degrees to unqualified overseas students in 2011.

PSA is not held hostage by international student markets and

the potential compromises they invite out of economic desperation. Thanks to

the financial liberation offered by PSA, the introduction of international

students is not be a matter of fiscal necessity, thereby allowing HE systems to

participate with integrity in the international market. Not only that, there can

be greater competition and perhaps concomitant reduction in the international tuition

prices, opening access to a wider range of socio-economic backgrounds, without

the fear of conflicts of interest that can lead to compromised institutional,

professional and personal ethics.

This is so because one of PSA’s improvements on the current

HEI model is its style of independent, anonymous crowd-source evaluation that

leaves no room for grade manipulation that favors higher GPAs and graduation

rates for top-paying (international) students. At the same time, if for the

price of domestic tuition, a professional academic can take on an international

student who has a low TOEFL or IELTS score and together they manage to achieve desirable

grades that are determined PSA-style, then all the better for both the academic

and the student – the only two essential denominators.

But let me pace myself, I should save discussion of some PSA benefits for Australia. To conclude with the Canadian data, revenue and expenditure are also revealing of the sort of financial liberation that PSA offers.

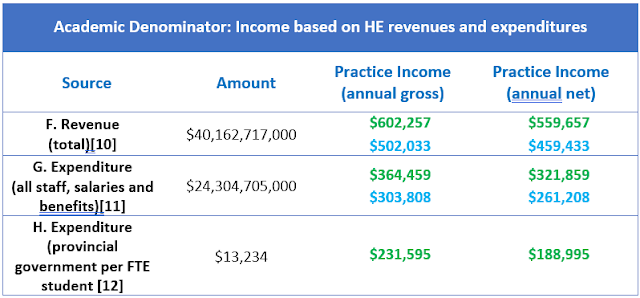

Provincial funding for universities per FTE student in 2019 is $13,234. Using the FTE ratio of 17.5, PSA academics can net $188,995 per annum. The total revenue for universities in 2019-20 is $40,162,717,000, of which 60% is spent on salary and benefits for all staff (i.e., administrators, faculty, and numerous types of support staff), which if paid to the 66,687 FTE teaching staff can net each of them $321,859 per annum. These are revenues that can easily support a private academic practice that operates under the protection and direction of a professional society of academics (PSA).

Two qualifiers are worth mentioning. First, all calculations

rely on a key academic denominator figure that is stipulated due to a lack of

data. Adjustment to this denominator will affect the practice revenue (or

practitioner income). Adjusting the 0.6 multiplier used to establish the FTE

academic denominator of 66,687 by two points either way to 0.4 and 0.8 will

result in FTE denominators of 60,127 and 73,247, and FTE teacher-to-student

ratios of 19.3 and 15.8, respectively. As an example of the effect on

practitioner income, using the Source A. “Average Domestic Undergraduate and

Graduate Tuition & Fees (PSA amenable FOS)” of $11,420, net academic income

is adjusted to $177,806 and $137,836 – compared to a net income of $157,250

based the 0.6 multiplier.

Second, all net incomes are calculated using the stipulated

practice expense of $42,600 per annum, which is chosen because it approximates

face-to-face education in HEIs. But in reality, because PSA is a professional

model, its fundamental service unit is a solo private practice for which expenses

can vary considerably based on practitioner prerogative. Professional academics

might choose more economical practice finances such as a home office, online

classes, less or no use of a GTA/GRA, or shared facility expenses through

partnership such as can be found in law, architecture, or medicine. In such

cases, the operational expenses are lowered, while net income is improved – all

without the burden of increased public or private funding of the system.

Objections

There are bound to be criticisms

rising in the readers: What about research? What about collegiality? What about

student social interaction? What about cooperation between HE and other sectors

such as Business or Government? What about big science? What about endowments?

What about collegiate sports? What about student admissions? What about

government oversight? And many more besides, since PSA is offered as a

comprehensive alternative to the HEI model.

Some of these criticisms are

addressed as this series continues in its analysis of Australian finances and

have been considered throughout this blog. For now, two rather obvious concerns

deserve attention: 1) The PSA model decimates employment for HEI administrative

and support staff; and 2) The PSA model cannot provide the scope of HE services

that HEIs do.

Where jobs are concerned, let’s

begin with a general comparison of the PSA and labour union responses to work

conditions within the HE system. First, unions only make sense where there are

antagonistic employers. Second, unions necessarily add to the cost of providing

HE, since their primary function is to negotiate continuous maximization of salary

and benefits (among other cost-raising items) for their dues-paying members. Third,

as unions represent only those dues-paying academics who have managed to get

hired by HEIs, their reach is short of academic labour that might otherwise be

available to the HE system.

By contrast, PSA has no employers,

unless you stretch the concept of employer to include the students who hire

academics or you stretch it even further to construe one’s self as an employer.

Second, PSA does not add to the cost of HE provision, it reduces the cost. Finally,

through professional licensure, PSA admits any and all qualified academics into

the HE labour force, not merely those academics who can be accommodated by the

inherent capacity limitations of the HEI model.

That said, the question of job loss

is complicated by the question of whether PSA supplants or supplements the

existing HEI model. If supplement, then as add-ons to (not hires by) an

existing university or college, professional academics cover the cost of their HE

services through the operation of a private practice. This places no additional

financial strain on the HEI, including its complement of institutional

employees. In fact, where professional academics elect to use the publicly

funded infrastructure of HEI facilities and services in the operation of their private

practice, there might well be an increase in HEI revenues and support staff that

accords with professional prerogative.

Where PSA supplants on a single institution

or system-wide scale, jobs are likely to be lost. Since PSA uses private

practice and professional society as the service model, this negates the replication

of numerous functions and so jobs across each and every university or college,

as demanded by the HEI model. These jobs include administration and certain

types of support staff. Of course, some of these jobs might be absorbed by the

range of private academic practices and the professional societies that replace

HEIs as the organizer and overseer – not the employer - of academic labour.

Unlike the HEI model, professional societies are not the antagonistic employers

of their members and render union representation moot, since a state-legislated

professional society acts as representative for all interested parties:

society, academics and students.

At the same time, as is true of

established professions such as law, medicine or accounting, PSA is capable of

wide distribution, relying on businesses and public facilities throughout the

community to meet the space and service needs of academics and students in

their mutually dependent HE relationship. As such, job loss is mitigated by those

continued needs. This is in stark contrast to the HEI model which necessitates negotiations

between HEIs and select businesses for commercial access to their campus-sequestered students. Consider how this video illustrates the possible benefits a distributive

PSA model can offer not only academics and students, but the wider business

community in which it is embedded:

This leads to the second of the criticisms that might be

launched against PSA. Though I have elsewhere detailed how PSA facilitates the

full range of non-institutional support work performed by academics in HEIs, it is worth

focusing on the institutional support work they perform as employees of

universities and colleges. At least to a certain degree, as a comprehensive substitute for the HEI

model, PSA might absorb discipline or profession-centered and institution or department-centered

work normally found at HEIs.

The Law Society of Ontario (LSO) is the legislated licensing body for lawyers and paralegals in the province of Ontario, Canada. Its functions include committees responsible for providing regulation and oversight of membership licensing requirements, investigation of and tribunal for complaints against members, ongoing professional development programs, along with initiatives to protect and educate the general public in legal matters. As of 2020, the LSO has 66,550 lawyer and paralegal members – essentially the entire FTE academic labour force for all Canadian universities.[20]

There might be further HEI work that finds translation in professional societies, such as participation in: promotion and tenure committees; faculty search committees; or reports related to departmental or institutional initiatives. However, there is much that is lost in translation here.

The LSO does bestow awards such as The Law Society Medal or the Human Rights Award, they review applications for licensure, and write reports on society operations related to initiatives, finances, and tribunals. But they don’t offer promotions or tenure, nor do they search for members. Entrance to and tenure in a profession are a matter of personal choice and performance. Nor is there any need to participate in other HEI-directed work such as: institutional promotion events; departmental meetings; senate and university council meetings; student convocation and commencement ceremonies; or institutional fund-raising events or campaigns.

Though I have repeatedly characterized HEIs as expensive, unnecessary middlemen, the present discussion might lead one to view professional societies as similar middlemen. They are not.

The annual expenses for the LSO totaled $230,993,000 in 2020, which was $10.9 million less than its revenues, even after a reduction in all membership fees for the same year.[21] By comparison, excluding the $6.001 billion spent on instruction and research, in 2019-20 Ontario universities – not colleges - spent $3.892 billion on: external relations; physical plant; administration and general; central computing and communications; student services; and academic support.[22]

Further, no matter what institutional support work one might think is transferrable from the HEI model to the PSA model, this is certain: All such work is distributed across a much larger body of academics and is being performed for only one or a handful of integrated professional societies across the country. This is in contrast to the HEI model where each of the over 100 universities in Canada uses its respective small cluster of academic employees to perform identical institutional support work – not to mention the work required by accreditation boards that essentially license HEIs to practice HE, as professional societies license practitioners. Because legal entities such as The Law Society of Ontario operate on a fraction of the funds and personnel that the university system requires, the HEI model cannot hope to compete with PSA where macro-level regulation, oversight, and “institutional” maintenance are concerned.

Finally, professional societies do not employ professionals, as HEI middlemen do academics. The third post of the series on the historical roots of PSA made it clear that professional societies are founded by practitioners – by lawyers, doctors, accountants, etc. – and that ironically, HEIs were founded by academic practitioners. If anything, such societies have more in common with labour unions than university and college employers. Whatever the institution promotional material might say, HEIs have some shared but also distinct and often antagonistic interests to those of academics and students.

The first thing to say is that one look at the list of work performed by

HEI employed academics reveals skills and knowledge that are highly

transferable to the operation of a private professional academic practice. This

is precisely the argument made by those groups within and without HEIs that

offer advice and service to PhDs who seek careers outside of academia.

Secondly, setting aside the qualified overlap and favourable

distribution of work already identified, any work that remains as unique to

professional private practice is budgeted for in PSA, including: a GTA/GRA and other support services

such as office assistance, accounting, janitorial, and the like. It is also

important to reiterate that the composition of private practice is a

professional prerogative that affords considerable variation in the costs and

that from the financial analysis offered here, it is clear that the expense of

operating a private academic practice is more than covered by the funding already

available to the HEI model. This means that much of the “new” work introduced

by private practice can be farmed out to the appropriate service providers,

should professional prerogative dictate.

In partial answer, this post closes by briefly comparing PSA’s facilitation of HE and the work of academics to two HEI attempts at facilitation: MOOCs and adjunctification.

Unlike the MOOC tech response, PSA can improve

student access to HE without eliminating face-to-face education, which offers

important benefits not easily reproduced in online formats. This is not to say

that technology is not of use to academics and students. It is to say that it

should be elective and used to improve face-to-face education, not replace it

out of some necessity caused by financial desperation that in the first place

creates the crisis in access and in the second is avoidable under PSA, which can

accommodate as many academics as the HE system demands.

It is also worth noting in this context that not only are MOOCs a direct challenge to the academic vocation, they also jeopardize administrative, management and support staff positions within the HE system. To a degree that has been acknowledged, PSA also jeopardizes careers, but no where near on the scale threatened by MOOCs – a threat to which unions have no hope of responding.

In light of such career jeopardy, though it might not be preferred by some, opening a private practice as a professional academic is a viable and perhaps necessary choice. In turn, under PSA the (increased) number of academics in private practice will require an array of support staff, if not administrative and management services, such as human resources, advertising, accounting, marketing and student recruitment.

Finally, as with MOOCs, the increasing use of adjunct labour reduces the full scope of academic work being done in the system, since its quality and quantity is metered by their working conditions, which are widely recognized as under-compensated and under-supported.

Also like MOOCs, the use of adjuncts is a desperate cost-saving measure of the current climate. As a viable alternative model, PSA can convert qualified adjuncts to academics that are properly compensated and facilitated in their contribution to the full spectrum of work they perform.

As always, I invite comment and collaboration on the PSA model.

Sources:

[2] Contract

U (policyalternatives.ca) (pg.18)

[3] The

State of Postsecondary Education in Canada 2021 (higheredstrategy.com) (pg.14)

[5] Canada’s

growing reliance on international students (irpp.org)

[6] Canada-Student-Financial-Assistance-Program-Statistical-Review-2019-2020.pdf

(pp.14-17)

[8] Office

Space in: University Avenue, Toronto, M5H 3E5 | Instant Offices

[9] University

(Regular) Members – CAUBO

[10] Revenues

of universities and degree-granting colleges (statcan.gc.ca)

[11] Expenditures

of universities and degree-granting colleges (statcan.gc.ca)

[12] The

State of Postsecondary Education in Canada 2021 (higheredstrategy.com)

(pg.37)

[13] Tuition

fees for degree programs, 2019/2020 (statcan.gc.ca) (pp. 6-7)

[14] Tuition

fees for degree programs, 2019/2020 (statcan.gc.ca) (pp.6-7)

[17] Tuition

fees for degree programs, 2019/2020 (statcan.gc.ca) (pg.4)

[18] The

State of Postsecondary Education in Canada 2021 (higheredstrategy.com) (pg.30)

[19] Feng, S. (2021) The Evolution of Shadow Education in

China: From Emergence to Capitalism. Hungarian Educational Research Journal.

11, 2, 89–100 DOI: 10.1556/063.2020.00032 (pg.94)

[20] Home |

Law Society of Ontario (lso.ca)

No comments:

Post a Comment