Part 2 provides further reason to criticize the AAUP team for the irony and absurdity of its response to what ails HE. The aim is to open the eyes of the AAUP

team to their folly and force proper consideration of the PSA model. It is

recommended that Part 1 be read before continuing, but the following content

can be managed without it.

PSA Offers an Alternative Response Apparatus

Continuing from Part 1 with the AAUP focus on academic

freedom and tenure, sustainable autonomy for the essential individuals of HE – academics

and students – is achieved not in idealization of universities and colleges,

but in emancipation from them. To achieve this, alternatives such as PSA must

be examined, especially in light of the most recent expression of

authoritarianism in HE and the self-defeating absurdities of the AAUP team

response.

In a PSA world it doesn’t make sense to say: There is a right-wing war on the Society of the PSA model. Is this an attack on the members of the Society, all of them, some of them? Is it an attack on the legal entity called the Professional Society of Academics? Or an attack on the professional service model it instantiates? Is the Society being too liberal in its treatment of members? Maybe the right-wing attackers want the Society to stop individual professional licentiates from teaching, researching or expressing one thing or another in their independent academic practices? We have ample examples of how universities and colleges flex over academics and students in the HEI model, but how exactly can the Society be used (by authoritarians) to control these individuals within the PSA model?

The Society part of PSA is not responsible for the individual. The individuals that comprise the Society are responsible for and to each other, as they are to society through the social contract of the professional service model – a social contract comparable to that of which universities and colleges are parties in the HEI model or the State Bar of California represents in law. The Society does not employ members. It licenses individuals to earn a living in fundamental conditions of professional independence. The Society does not admit students to HE nor does it control the students who seek HE services. Students are free to seek the services of academics, as academics are free to provide services to students. In this exchange, along with civil and criminal law, insurances and assurances are provided by the Society to protect the parties – as university and college middlemen are meant to provide in the HEI model or the Medical Board of California is meant to provide in medicine. Without making it a condition of employment or career advancement as the HEI model does, academics are free to pursue whatever research they wish without scrutiny or sway from an institutional employer, as they are free to pursue no research in their practice (beyond that demanded by competent teaching and community service within their fields). The Society does not interfere with the constitutional rights and freedoms of academics and students – certainly not for preservation of university or college brand and bottom-line – as this is an absurdity that amounts to self-interference in a professional model.All of this is in stark contrast to the HEI model where institutional employers interfere with their faculty employees and student admittees in almost every aspect of HE provision, resulting in: civil, criminal, and union action; public speaking and social media employment contract clauses; institutional codes of student conduct; op-eds; recommendations; demands; reports; violations of academic (research) integrity; even Congressional hearings.

The Society part of PSA is not so burdened and so the academy is not so burdened. The PSA academy is empowered to function as Anthony Paul Farley describes in the Academe:

Higher education places the entire society in which it takes place on trial. Education indicts the commonplace notions upon which society is built. Its purpose is to produce people who question everything, especially the commonplaces. James Baldwin argued that although “no society is really anxious to have that kind of person around,” having such people around is “the only hope society has.” Higher education produces this hope and is therefore a public good.

For all their righteous rhetoric about HE as a public good, the AAUP team would do well to heed these words. The team has fallen for commonplace notions of HE and how it is provided, when duty demands they question everything. The failure here is intellectual, professional and moral.

It is true that the Society has leverage over its members through such things as licensure, discipline, and anonymous crowd-based, academic peer-based evaluation, any one of which can negatively impact the ability of academics to contribute to and earn a living in the academy. But this is power that can only be defined and exercised by democratic consensus among the Society members – among whom are not included, institutional employers, board governors, corporate investors, wealthy donors, or bond holders. Perhaps the Society members decide not to subscribe to the recommended objective crowd-based, academic peer-based evaluation of the PSA model – after all, the HEI model has been operating without meaningfully objective evaluation for centuries. If so, then so be it. Or, should members democratically decide that pro-genocide rallies among its licentiates is grounds for professional censure, sanction or expulsion, then so be it.

But notice how this returns us to the salient AAUP point alluded to by Schrecker in Part 1, that the only ones with the requisite competence to exercise authority over HE are academics. Notice also that if PSA was the model for HE, then it would be a strain to speak of what Ruth called in Part 1, (sub)authoritarian rule, where in this case authorities rule over the authorities. At any rate, it would be far more difficult for authoritarianism to arise in a HE power arrangement devoid of the HEI model cadre. Again, in stark contrast, such authoritarian flexing routinely occurs in the traditional toxic mixture of relevant and irrelevant, conflicting and complicit, interests and authorities that comprise the power structure of universities and colleges.

Should there be an irreconcilable falling out among the academic members of PSA, then the divided groups can legitimately form their own professional societies and provide service to the community according to their respective expert authoritative visions for HE. The New College of Florida example imperfectly demonstrates exactly this sort of schism. It is imperfect because the best the rebellious academics and students of the newly formed Alt Liberal Arts could do was seek shelter under the umbrella of yet another accredited HEI (Bard College), leaving them with only a non-credit learning platform and the hope that their new home doesn’t fall prey to similar (illegitimate) external or internal interference. Were PSA in place, there would be no need for such personally hazardous and professionally feeble actions, since academics are licensed to independently practice HE, form their own academic partnerships, issue credits toward recognized degrees, and where necessary even form their own Professional Societies of Academics in response to substantive practice or ethos misalignment among members.

Academics are the only qualified proper authority to oversee

HE, which strongly implies they must oversee themselves, as the legal and

medical professions recognize in their own qualification for self-authority, qualification, that from the perspective of PSA, is acquired with bitter irony through

the qualified HE services of academics who are forced to be faculty employees. As indicated in Part 1, this sort of

happens in the HEI model of accreditation. What PSA does is replace the

indirect self-oversight of institutional accreditation through third-parties with the direct

self-oversight of individual licensure in the professional model of first-parties to the social contract. This replaces

the reactive AAUP-cum-union representation of faculty employees with the

proactive professional self-representation of licensed practitioners. This tested,

rational, structural distinction results in massive improvements across HE, as

argued across this blog.

So much for yet another take on the superiority of PSA over the HEI model that the AAUP team champions. But if this doesn’t convince you to consider the PSA model as a serious contender for HE provision, then consider further reasons to question the HEI model as the reigning champion.

PSA Avoids Absurdities of the AAUP Team Dream

Absurdity lies in the fact that the AAUP team validates

their existence through efforts to protect the exercise of the fundamental HE

values of academic freedom and integrity, while their efforts serve to

undermine the exercise of these values. Part 1 showed how PSA is superior to even

the dreamiest of HEI models and how the AAUP team needs to return to its roots

as advocates for the profession, not bargainers in the HEI (employment) model

it blindly assumes. They need to do this because before them is an alternative model that avoids absurdity, one they ignore, and by doing so make themselves

complicit in the harm done to everyone who depends upon the HEI model for the social good of higher education.

But this embarrassment of absurdity and complicity gets

still worse. The AAUP, AFT, CUCFA, SFNDHE, and the rest of the team that

pursues their version of ideal HEIs have unwittingly always been on a path to

PSA. Though the team members are unable to see to the horizon beyond HEIs,

their position, passion, prosecution, and protest are all derivative of the

professional service model of PSA.

I have argued this point elsewhere on the blog, so consider

here a synopsis: A history of cyclical fighting over shared

governance in the HEI model fundamentally involves employers and employees

arriving at a tolerable formulation and trustworthy execution of authority

distribution with respect to operational aspects of universities and colleges

in the provision of HE services. A kumbaya calibration is one where academics

exercise authority that is at least equal to that of their institutional

employer, its board of governors, and other interested parties of the HEI

model, especially in matters related to frontline academic service such as

teaching and research. But the preferred calibration for team AAUP is something

along these lines: we academic employees will do our work as we see fit, you

institutional employers will pay us (well), leave us (largely) alone, and we

will contact you if we need something.

A possible instantiation of the PSA model arranges things this way by essentially reversing the roles, with HEIs serving as vendors for professional academic practices. According to the fundamental utilitarian nature of HEIs, in the operation of their professional independent practices, PSA academics might elect to lease or purchase various assets and services from universities and colleges, such as office and lecture space, computing and printing services, microscopes and manuscripts, etc. This is feasible, since HEIs already generate revenue through such sales and, as public investments, universities and colleges are ultimately subject to social changes in the arrangement for HE provision. This take on PSA underscores the elective nature of HEIs, since independent academic practices can secure operational provisions from other suppliers throughout the community, including from their Society, all of which with the HEI vendors must compete.

Whatever the place for HEIs in a PSA world, if we eliminate

governance directly related to institutional operations, the remainder is that

over which the AAUP team principally seeks authority. In a PSA

world, this authority is not sequestered from or shared with institutional

employers or governing boards or accrediting agencies but with the fellow

academic members of their legislated Society. This authority calibration is in

line with how Schrecker describes the professional standing and HE ethos that

the AAUP team seeks:

From the beginning, the AAUP embraced academic freedom as the rationale that would not only preserve the faculty’s professional standing but also guarantee the autonomy and integrity of higher education by enabling professors to do their teaching and scholarship limited only by the parameters of their disciplines and the judgment of their peers.

Right, what PSA calls professional academic practice and

what the AAUP team calls tenured faculty employment, while neither makes mention

of universities or colleges. How does this difference between the PSA and HEI

models relate to shared governance?

Imagine that on the far left of a governance slide rule you

have employees with no say in how their employer steers the institution or

company that cuts their paychecks. A few notches to the right you enter a range

on the rule where the employer and the employee jointly steer with greater or

lesser degrees of distinct and binding mutual authority. On the far right you

have employees that steer the institution or company with no binding input from

an employer.

The efforts of the AAUP team aim to settle matters in the midrange, where HEIs hire academics, promising some level of binding shared governance, academic freedom, and (tenured) employment, which often proves disappointing and so labor unions are brought in to better arm academics for combat over calibration and administration.

But now consider a less familiar very far right setting on

the governance slide rule, where PSA resides. PSA offers a space in HE where

there is no need for HEI employers and so no need for union armaments. Instead,

academics are licensed to offer their expert services in solo or partnered

practice, under the self-governance of their own professional society that

protects and directs the HE service that members provide. In a model of mixed interests

that frequently pit institutions and individuals against one another, unions

want to wrest greater control over working (or studying) conditions for the

labor (or student) groups they represent, but unions are merely another competing

set of interests in the HEI wrestling match. PSA reduces the number of

competitors in the tournament, by removing the need for an institutional cadre

and reintroducing independent work to HE after centuries of absence.

This takes the AAUP team preferred governance calibration to

its logical conclusion, bypassing antagonistic placard waving over the

constitution, operation and direction of HEI employers, because there is no need of

universities and colleges. To borrow from Schrecker, PSA protects

academic freedom, establishes and

To be clear, PSA is not a utopian academy bent on the

wholesale elimination of HEIs. Though some academics might be

drawn to professional independent academic practices that form service

relationships with HEI or other community vendors, there will undoubtedly be

academics who would rather remain a university or college employee, and

certainly tenured employees are likely to prefer the status quo. Even

in the established professions, plenty of lawyers and physicians have elected

for career paths as employees rather than independent practitioners - but do notice how these (actual) professionals have the option, the choice, while academics do not.

Of course, electing for HEI employment will perpetuate the

centuries-old struggle with academic authority and working conditions, insufficient

and inequitable access to HE, illegitimate outsider interference, technological

threats to the vocation of academic, and the common response apparatus of

pandering, protesting, op-eding, recommending, demanding, Congressional hearing,

union acting, and other ineffective V-ing. To these consequences can be added

that if PSA is in place, then HEI employers will also be competing with professional independent academic practitioners who provide HE services not

under the authority of universities and colleges, but perhaps with the tables turned and HEIs as the ones contracted by the academics.

Nevertheless, said sincerely in the spirit of autonomy that

PSA embodies and enables: Good luck staying the familiar course of HEI faculty

employment. As a recommended means by which to eliminate the exclusivity of

institutional academic employment in HE, PSA does not promise that earning a

living in the professional model is more secure than HEI employment – I have

owned and operated businesses, so I know firsthand that such independence is

chancy and challenging. As a result, many, maybe most,

academics who count themselves lucky enough to be employed (however precariously)

in the HEI model will not want to be professional independent HE practitioners –

though the adjuncts who use their cars as offices and apartments might not count

themselves among them.

Nevertheless, in the same spirit of autonomy, there are no legitimate grounds upon which to deny the PSA model official footing and certainly none to deny it a proper hearing by the academy. Seduction of the HEI model notwithstanding, qualified academics who are within or without the exclusive institutional employment arrangements of the HEI model should not be denied the option, the opportunity to practice HE as independent solo or partnered professionals. PSA makes it possible for not only the blessed or the blighted few but all academics to exercise their right to earn a living in HE after years of personal investment in career and community.

In contrast, the AAUP team champions institutional shared

governance, where parties to the sharing are routinely in conflict, one party

employs the other, and parties external to the institution regularly interfere –

and where there is no alternative like PSA to act as a counter to imbalances.

Under such employment circumstances, the AAUP team naturally seeks protection

from the limited, uncertain, unsettling nature of earning a living in the HEI

model. To achieve this, the team principally champions tenure. The expectation

is that with tenure academics can securely exercise not only academic freedom

but also authority in the shared governance of their employer, somewhere in the

midrange of the governance slide rule.

It should come as no surprise that tenure is the foundation of the AAUP team dream for the HEI model. It should come as no surprise that in the end this discussion is about employment security, or put in more general terms, the security to earn a living. This was also true for the attorneys and physicians who acted to establish legislated professional autonomy to earn in a comparison worth noting for those with romanticized notions about academics and vilified notions about the established professions.

For emphasis, the team claims that within the HEI model the

exercise of academic freedom and shared governance is necessary for proper HE

service and that all depend upon tenured employment for their proper protection

– though its growing profile as a labor union suggests a contract that garners

a majority “yes” vote qualifies as an employment security victory to the AAUP. As Schrecker says in her AAUP retrospective,

Even so, violations of academic freedom were commonplace. I know of more than one hundred people let go for their political activities during the 1960s and early 1970s, and it is likely that there were hundreds more. Still, given the attention the campus troubles received, there were surprisingly few high-profile dismissals of tenured radicals. Most of the people who lost their jobs for political reasons during the sixties and seventies were junior faculty members lacking tenure and not reappointed for ostensibly “academic” reasons. Unless their dismissals involved particularly flagrant violations of due process, the AAUP rarely took their cases. Nor was it asked to.

Setting aside nuances of the disputed employment security offered by tenure and that PSA claims institutional employers, shared governance and tenure are neither required nor recommended, the AAUP association sideline and labor union advocacy for tenure might seem natural and noble. But it is absurd.

If tenure is needed for proper provision of HE services within the HEI model, then does it make sense to say it is earned? Does it make sense to establish probationary periods and hurdles for its attainment? No academic is hired with automatic tenure. Instead, a fraction of faculty employees are fortunate enough to even ride the tumultuous tenure track to a terminal of peer review and often administrative approval.At the same time, it follows that from day one all academics

in the HE system must possess employment security of the sort provided by

tenure in order to properly perform the job. In reality, some 70-75% of the

faculty employees of HEIs in the United States are hired without being given many

tools for the job, including tenure – with similar statistics in other major HE

systems of the world. The statistics on tenure vary, but being generous around

one-fifth of the faculty have this necessary tool for the job.

With all of this on the table and having recognized as far back as 1978 that contingent faculty employment is “inequitable, harmful to moral, and a threat to academic freedom,” it stands to reason the AAUP team should advocate for an HEI model where upon hire tenure is granted to all faculty employees and very likely also to academic support staff such as graduate teaching and research assistants. But as James G Andrews describes in the Academe, what it in fact proudly settled on was a seven-year probationary,

limit that has remained the most widely accepted national standard, irrespective of academic institution and academic discipline, since it was initially adopted by the AAUP and the Association of American Colleges (now the Association of American Colleges and Universities) in the widely accepted joint 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure. Most informed observers would agree that it is reasonable to insist upon satisfactory faculty development during a probationary period of some significant duration before granting the special privileges and corresponding obligations associated with tenure. The rationale for a substantial probationary period is that it provides adequate time for a well-qualified, highly motivated, and adequately supported candidate to establish the sort of record of achievement in teaching, scholarship or creative work, and service needed to justify a tenured faculty appointment. At issue here is the upper limit that should be placed on the probationary period.

This has the feel of a reasonable labor negotiation point, only one where the employer and the employee settle on an absurd contract clause: Both parties agree academic freedom is a necessary tool for the job and that tenure is a necessary condition for the proper exercise of academic freedom, then both sides negotiate a seven-year probationary period during which the employee does not have tenure but is expected to demonstrate “satisfactory faculty development” in order to apply for the tenure that is necessary for their development and performance in the job – and this doesn’t address the fact that the majority of faculty employees are not even on a track that might lead to tenure, no matter their demonstration of progress or proficiency.

The AAUP will object by pointing to how the “250 scholarly and education groups” which endorsed the 1940 Statement of Principles agreed

that, “During the probationary period a teacher should have the academic

freedom that all other members of the faculty have.”

To the sensibilities of academics in the past 40-odd years

there is a shifty vagueness in this principle, one corrected by replacing “all

other members of the faculty” with “tenured members of the faculty.” After all,

what other employment distinction matters in this context?

To which the AAUP will object by pointing to the 1970

addition of an “interpretive comment,” that is not in fact interpretive but rather

the sort of thing one finds in a labor contract:

The freedom of probationary teachers is enhanced by the establishment of a regular procedure for the periodic evaluation and assessment of the teacher’s academic performance during probationary status. Provision should be made for regularized procedures for the consideration of complaints by probationary teachers that their academic freedom has been violated. One suggested procedure to serve these purposes is contained in the “Recommended Institutional Regulations on Academic Freedom and Tenure,” Policy Documents and Reports, 79– 90, prepared by the American Association of University Professors. [Italics added.]

This 30-year-old after thought is right on time for the AAUP

transition to its labor union role and actually has nothing to do with the

enhancement of academic freedom since no new articles of freedom were added.

Instead, what was added were procedural suggestions for how to protect the

academic freedom of those with tenure-track probationary employment status.

This is an attempt to equalize the protection for academic

freedom that is available to full-time probationary (or tenure-track) and tenured faculty employees. It is

an obvious failure. After all, if the two employment statuses enjoy the same employment

security and protection, then why are we having this discussion? If

the security and protection are on a par, then why is there a distinction in

employment status terminology? Why is there a seven-year probationary period?

Why has the AAUP morphed into a labor union? Why is there an Eighth 1970 Interpretive

Comment?

The 1970 suggested procedure does nothing to interpret and virtually

nothing to ensure academic freedom for those academics who find themselves on employment

probation of one form or another, as compared to their tenured faculty

counterparts. This AAUP attempt to salvage an obviously absurd HEI model employment

arrangement is like providing a builder with a hammer that approximates a

properly working version of this necessary tool for the job, but it has a bent prong

on the claw and a slippery grip. Upon issuing the hammer the contractor assures

the builder: Don’t worry. The hammer works perfectly well. You can swing and

pull as you see fit in the development of your skills and completion of the job.

If we as the contractor or the clients have any complaints about your work,

then we can collect some suggestions for work-arounds that compensate for the tool

being subpar compared to the properly working hammers of the other builders on

the job site.

There is no need for such absurd contortions in PSA. There is no should be, no we hope, no we suggest, no we negotiate for “regularized procedures” to hear complaints of academic freedom violation or for “the periodic evaluation and assessment of the teacher’s academic performance during probationary status,” which has the obvious real potential to undermine the exercise of academic freedom in the job for which the performance is being evaluated and assessed. These are contortions fraught with potential and actual fiasco, all meant to help prop and manage the unquestioned tradition of the HEI model.

This quagmire is created in large part because, to borrow a

rhetorical device from Andrews, “most informed observers” fail to recognize their underlying assumptions, such as that HEIs are necessary for HE provision or that

HEIs are identical to HE. Both assumptions are false. Both assumptions inspire

absurdity, along with wasteful behavior such as the AAUP team defense of

institutional academic freedom, which, given the falsity of the assumptions, is

a classic case of category error reasoning. Institutions don’t need academic

freedom, academics need it, to do the job for which they were hired by institutions

that often work to undermine the academic freedom of their faculty employees. Dizzying.

But suppose the AAUP team launches a national campaign for universal

tenure upon hire, with no probation. This would avoid the embarrassing employment security absurdity,

but “most informed observers would agree” this form of employment security is unattainable

and undesirable.

In China, one type of employment security is renyuan bianzhi

(人员编制), which

is commonly called, bianzhi (编制) or the iron rice bowl, and

can be translated as, “the optimal number of workers needed for the job.” The

Chinese Communist Party (CCP) hires people into the bureaucracy or state-owned

enterprises, including the entire education system, and after sufficient

demonstration of loyalty to Party cadres these employees enjoy well-above

average incomes and lifelong employment with virtually no chance of being

terminated – though as the recent downturn in the Chinese economy has shown,

the bowls are cracking and for those who manage to retain their lifelong

employment, this does not mean a lifelong living wage. In the Chinese HE system you earn bianzhi. In the Western HE system you earn tenure. In both

systems rice bowls are available, but most wait in line peering through the

window from the street with chopsticks in hand.

PSA offers improvement to any HE system that uses the HEI

model, and so, when still in China, I wrote a post naïvely thinking that PSA

might be used to help address the serious inequities, exploitation, corruption,

and poor quality of the CCP HE system. But the reality is the Party would never

dream of relinquishing its authoritarian hold on state-owned HEI engines for

growth and graft. Communist Party Committees – which are required in

all HEIs (and “strongly suggested” for all private corporations) and which oversee

compliance with Party wishes – are now being merged with the Office of the

President for all universities and colleges in the China HE system. The country’s

flagship Tsinghua University underwent this major buff in authoritarian rule

last year. Unfortunately, it is not a rhetorical comparison to say that this is

comparably true in the West, as is made clear by the history of HE, Schrecker’s

review of the AAUP, and the current iteration of political

authoritarianism in HE systems across the United States and other western

countries.

|

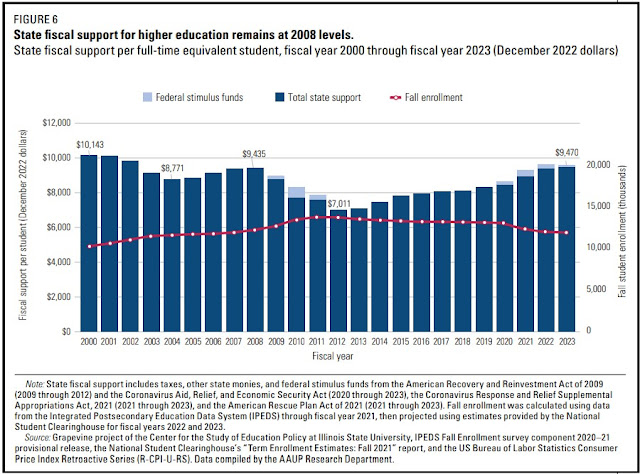

| Academic Freedom Index 2022 |

In this way, universal tenure upon hire is unattainable in the HEI model, where powerful interests oppose such a calibration, and not entirely without good reasons. After all, financing such a hiring practice would further strain a model that even in the best of times faces access and funding challenges, when access should be expanding. But it is the loss of authoritarian control over the principal labor that makes this suggestion a tough sell. PSA faces the same tough sell, though it has the advantage of professional precedent, substantial systemic cost-cutting, and unprecedented benefits to all stakeholders.

Universal tenure upon hire is also undesirable because it

limits both the quality and quantity of academics and their support staff of

graduate assistants that can service society. With respect to quantity, the largest

aggregate expense of HEIs is (faculty) employee salaries and benefits,

accounting for 20-30% of the operations budget, depending on which HE system or

institution is being examined. This is so even though there is at best a 3-to-1

ratio of contingent to tenured employment in the HEI model and an even more

shocking 1-to-100+ ratio of graduate assistants to students, with the former in

both ratios being poorly paid and benefited. This operating expense will only

increase as unionization succeeds in extending improved compensation across the

sector, and would be staggering if renyuan bianzhi (人员编制) were achieved across

faculty and graduate assistance employment.

This increase in operation expenses is undeniable, though various

organizations on the AAUP team think it insignificant. For instance, in the

2016 issue of the Academe, the AAUP claims,

If institutions of higher education are to excel over the coming decade, colleges and universities must develop plans to convert part-time non-tenure-track positions to full-time tenure-track positions. The AAUP hopes to lead the way in helping institutions develop these plans, which can be undertaken at an additional average cost of 2 percent of institutional expenditures per year.

With now less than three years left in the “coming decade,” it

doesn’t look like anyone is following the AAUP lead – a lead that anyway has

been shown to be absurd. So much for hoping and helping. Over and over the same

tired moves are made with complicity. My counter move is a dramatic reduction

in the financing required for HE provision, not to mention the other

wide-ranging improvements PSA offers. Check.

Measuring the AAUP plan on its own merits, there is little room for hope or help. Even if the administrative bloat of HEIs were put on a crash diet, the full complement of HEI model operations remains and it is reasonable to think that more of this institution-oriented work – not directly related to teaching, researching, and community servicing – will be placed on the faculty employee plate, which would then require an expansion of universal tenure upon hire faculty employees and the funding necessary to properly compensate them.

Some have suggested savings can be had by moving to a leaner model, reducing the ever-expanding range of non-academic services that universities and colleges consider identical with the college experience of HE. To which I say, keep coming you’re almost here on the PSA side. Like the AAUP team defense of academic freedom and shared governance, such thinking logically leads to the professional service model – that is, unless one is obsessed with preservation of universities and colleges, whatever these terms might mean under a new lean conception.

Setting aside speculative increases in faculty workload, the

AAUP plan for employment security is necessarily limited by the

employment and facilitation capacity of university and college employers. As a

consequence, the number of faculty providing HE services is likely to go down

due to rising labor costs, when the number needs to go up. For some time now in

a place like California, once considered a premier HE system,

hundreds-of-thousands of qualified students cannot access HE in locations or

programs of their choice and in most cases of their tax-paying right – with the

numbers soaring to the 10s-of-millions where the HEI model is considered in its

global geography. Further, from the point of view of a career in

the academy – something with which the AAUP team is principally concerned – a

move to virtual rather than brick and mortar facilitation will not be a welcome

solution to the capacity problem, since online HE requires even fewer faculty

employees. The virtual version of the academy presents its own slue of problems that PSA effectively addresses.

But perhaps the most serious problem with the AAUP plan is that it suffers from the same defects as tuition-free or expense-free HE plans that assume the HEI model – including one I criticized from the Lumina Foundation and faculty employees, Sara Goldrick-Rab of Temple University and Nancy Kendall of University of Wisconsin-Madison, and which was popularly referred to as, F2CO. In a nutshell, a major defect is that all such plans call for an increase in strings-attached funding that has repeatedly proven to be vulnerable to economic, political, and social interruption, in a system with a capped faculty body (and universal tenure upon hire). Even if the funding were made available, this is irresponsible, unsustainable stewardship of HE.

To repeat for those on the AAUP team who respond to the problems we face in HE with a dreamy

narrative of autonomous shared governance employment, uninterrupted sufficient

funding, and unlimited secure employment and study access, even if the dream

comes true, PSA remains the superior model (see Part 1 for this argument).

|

| SHEF State Higher Education Finance FY 2022 |

As for quality, the AAUP team assures tax-payers that on the whole tenured professors are highly productive. Of course, this is a self-selected group with the will to march the long and uncertain track to possible tenure. But no matter their employment status, there is evidence that most academics tend to work a solid week, ranging from 40-60 hours in the United States and Canada. This is just the sort of work ethic and conditions one finds in entrepreneurship or the professions where practitioners own and operate their own independent practices, with attorneys typically working 42-66 hours per week.

That said, praise for the work ethic of academics is unlikely to convince taxpayers of any political shade that employment probation should be eliminated and that the lifelong employment and income security of tenure should be unconditionally handed out to all. So, while the AAUP team offers absurd, self-defeating, unattainable, undesirable tenured employment, PSA offers a professional licensure solution that avoids triggering prudent resistance among taxpayers, because the professional model does not hire academics. PSA licenses, supports and disciplines academics in the provision of their HE services on the open market.

‘You mean evil market!’, I hear, as the cries from

cardboard conceptions of neoliberalism drown out the sounds of reason. But

cover your ears and follow me a little farther.

In the HEI model for undergraduate studies, each semester faculty employees enter a virtual or real classroom where 20, 50, 200, 1000, even 100s-of-thousands of students appear from the admissions ether. Complete strangers to each other, they begin the intimate service of education, while in faculty lounges casual comments are made about the quality of this year’s batch, if students are discussed at all. Sounds ideal, what could go wrong?

In contrast, graduate evaluation and admission best

practices in the HEI model indicate the value institutions place on the

integrity, quality and success of graduate education. As PSA borrows from the

professional service model it also borrows from the HEI model. This is evinced

in its adoption and adaption of the admission and evaluation practices common

to graduate studies. One PSA adaptation introduced in Part 1 is the anonymous

crowd-based, academic peer-based evaluation of all student work and evaluation

materials used in assigning final grades. Here the focus is on admissions.

PSA academics exercise professional prerogative with respect

to the HE service they provide, while students select the academics from whom

they want to receive HE service. In both cases the choices are properly

individual and informed – without the obstruction of unnecessary university and

college intermediaries. For instance, the Society part of PSA provides students

with information on academic practitioners, including publication of practice

performance metrics such as: 1) pass/fail ratios; 2)

student evaluations of service; 3) academic peer evaluations of service; 4)

disciplinary/commendation actions taken by the Society; 5) criminal records; 6)

number, level and profiles of students serviced; 7) types of professional

development; 8) areas of teaching and researching specialization; 9) student

post-service success/failure data; 10) community service; 11) qualifications; 12)

awards; 13) research record; 14) years of service; and whatever other data students and academics deem useful in exercising their agency to make

informed decisions about which education and research relationships to form. PSA

also provides academics with information on the students who seek their

services such as that which is found on any university or college application:

GPA, letters of recommendation, awards, personal statements, transcripts, etc.

This is not the only information that is made available in the PSA model nor is this a complete description of how this information is collected, managed and accessed for service and stewardship purposes. But clearly, possession of this type of information enables academics and students to better select with whom to form HE service relationships.

This use of information architecture is largely absent

in the HEI model, since institutional recruitment marketing campaigns play the

predominant role in swaying application decisions – though, again, it is

notable that faculty information takes on a larger role when students apply to

graduate school. Likewise, the faculty that provides frontline service (70-75%

of which are adjunct) have no meaningful input into admissions or student class

selections – though again, it is notable that student information takes on a

larger role when admitting and mentoring students at the graduate level of

study.

If a PSA academic repeatedly or egregiously fails to provide

satisfactory service, then students (and colleagues) can know from (inter alia)

the public practice performance record. Should such academics not improve their

service through professional development of the sort offered by PSA, then they

wither out of a career in HE teaching, as students will not select them for

service and no selection means no (teaching) income. Similar market mechanisms

are at play when it comes to forming graduate or colleague research

relationships.

The phrase, “market mechanisms,” is likely to cause

anti-neoliberal hackles to flare. But what is being described here is neither

nefarious nor alien. In fact, these are ideal circumstances for making service

choices. At any rate, they are common, like asking friends for a therapist recommendation,

searching the Public Records of Attorney Discipline when selecting an attorney,

or consulting the institutional rankings, marketing materials and faculty profiles

when sending out college applications. We want to give our money to people who

can do for us a satisfactory or exemplary job and we have a better chance of

succeeding at this the more information that is possessed by both sides of the

service equation.

For sound reasons, psychotherapists and attorneys routinely make their own determinations regarding the suitability of forming a service relationship with those who seek their services. The service of education is not like that provided by a mechanic or a builder, where the person paying is passive, even irrelevant to the outcome of the service relationship. In education, as in other services like fitness training, medical care, legal counsel, and marriage therapy, the quality of the outcome significantly depends upon the quality of participation by those seeking and paying for the service. In PSA, this is why market mechanisms such as profiles apply not only to academics but also to students and so a scholastic profile for students is used to inform academics in their own selection process.

In both directions, the individuals are informed well beyond

the ether emissions of institutional admissions and can better ensure a

successful education service relationship. This is a model where the

expectations of academics and students are interdependent, not as some

your-success-is-our-success marketing slogan, but where a successful education

relationship benefits both, while an unsuccessful relationship harms both.

The AAUP team dream unwittingly requires tenure for all as

protection for shared governance, academic freedom, integrity, and ultimately

the quality of HE. In this last regard, tenure releases faculty employees from pressure

to pander to student or employer expectations, enabling them to assign the

grades that students earn – departmental pass/fail ratio data be damned. In this way, faculty employees can maintain education standards,

albeit highly idiosyncratic standards, without concern for employment security. Of course, in the dream academy tenure also enables them to abandon standards.

In contrast, the PSA model protects the quality of HE, not by immunizing academics against the poor or failing grades of their students, not by marginalizing their role in the education and evaluation equations, but by directly binding the success of academic practices to the success of student studies, in circumstances where self-serving and idiosyncratic evaluation practices are tempered by the PSA-adapted evaluation practices of HEI graduate level studies.

In this way, (taxpayer) reservations regarding universal

tenure upon hire are addressed: There is no tenure except that achieved through

the consistent provision of quality HE services, based on publicly available

information that better informs service selection and objective evaluation

practices that avoid corruption of education standards and academic integrity,

in a model that does not rely on limited employment opportunities, unqualified

employment security, and a systemic disconnect in the expectations and

consequences of the education service relationship.

Elsewhere on this blog I have described PSA as liberal with a dash of neo. If after all of this, you spit on the ground and

utter dirty neoliberal, then I tip my hat and wish you luck in the quest

for sustainable solutions to the many serious problems of the HEI model. But if

you are still with me, let’s continue.

It is important to underscore that “employment security” and

“income predictability” are not synonyms, and that no vocation guarantees

lifelong employment and income security. This is the starting point for

discussion of how to best ensure the academic freedom and integrity that is

necessary for proper HE. Anything else is fantasy.

That the PSA model eliminates tenure while it better

protects academic freedom and integrity must strike the AAUP team as absurd. But

this is because for centuries the common conception of HE provision has been steeped

in the HEI model. This is an assumption we can no longer afford to harbor. Given

the fierce obstacles and uncertain future we face, the academy can no longer

afford its intellectual conservativism. The AAUP team has not embraced this

reality.

In the face of diminishing tenure-track and increasing

contingent employment across HE, these days the AAUP team responds to the

foundational issue of employment security by flexing its labor union side. In some ways this is an improvement, but whether it is a contract for one

course in one semester or fulltime faculty status over several years, whether

it is an hourly wage or a salaried arrangement, these do not offer to academic

freedom and integrity the employment security that comes with tenure. A

multi-year fixed contract can provide short-term income predictability, but

this does not eliminate the tenuous nature of the employment.

Perhaps the AAUP team hopes they can help by contributing to

a growing worker solidarity movement, uniting workers across vocations and

locations. Certainly, there is good reason to act for greater

proletariat power with respect to working conditions across the board, and a

professional model like PSA is in line with such aspirations. However, for

purposes of this discussion, it is important to acknowledge reality checks like that offered in 2023 by one of the most powerful unions on the planet, the

United Auto Workers, when it negotiated a contract with: behind the scenes

deals between Fain and Ford in violation of democratic principles; wage gains

less than half those forfeited during the 2008 recession; 30.7% of Ford and

45.3% of GM workers voting against the contract; and more that leaves the

proletariat with a mixed message of victory over the capitalist exploiters (in

an environment where it is no longer even fashionable for unions to use such anti-capitalism

language).

In the present context of advocating for professionalization (in contrast to unionization) it is also important to note that there are significant distinctions in the types of work being brought under the union banner. The work performed by academics is more like that of Hollywood writers or building architects than Starbuck baristas or automotive workers. The similarities between the 2023 Writers’ Guild of America strike and AAUP-cum-union responses to troubles in the HEI model are a striking example – though not for the, “Rah! Rah! Solidarity!” headlines over which union leaders salivate. Much like the essential role of academics and the inessential role of HEIs, writers are essential while studios are inessential. As is the case in the HE industry, this was so from the beginning of the film entertainment industry.

Be they academics or authors, the worker options are the same: 1) Take the conditions dictated by the capitalists; 2) Take action on (union) threats to withhold work from the capitalists; and 3) Take the work and walk away from employment by the capitalists. Over the first and second, PSA enables the third for HE and recommends the same for Hollywood.

Part of the reason for this is that some labor and capital is essential to any industry, while others are not. In the film entertainment industry, for illustration an incomplete list of capital and labor includes: cameras, camera operators, and writers. It is true that the camera and (perhaps) the operator are essential to film, but without a story to tell there is no entertainment and so no use for the camera and operator in the film entertainment industry, while the writer can tell the story using another (broadcast) medium.

Of course, as technology

advances the operator and the author face the threat of replacement by the

capitalist – a key negotiating point in the WGA contract. All of this is

analogous for the HE industry, making the choice between the professional and

union models obvious, since academics (or authors, actors, etc.) need to wrest

more control of their work from the capitalists who employ and replace them.

This is the function of capitalism-bound labor unions, with the obvious extension

of this control being something like cooperative ownership or professional independent and partnered practice.

As such, in Hollywood the essential labor should walk away to form independent studios that are cooperatively owned by essential labor such as writers, directors, and actors, thereby erasing all worries about technologically generated scripts, actors, and other profit enhancing measures used by the capitalist studio employers. This walk away approach is what PSA advocates for HE through professionally licensed independent or partnered academic practices. In both cases, the essential labor is empowered to protect and nurture its own interests, eliminating the need for unionization and eliminating or vendorizing the unnecessary middlemen in Hollywood and HE. In this way, PSA offers greater worker empowerment than the neoliberalist, capitalist, unionist arrangement of the HEI model, especially where the HE industry is properly public and not for profit.

So much for attempts to salvage the historically rooted institutional employment approach to academic governance, freedom, and integrity that ensure quality HE, in a model where tenure and paycheck (and all that this affects in life) depend on the probationary union-mediated relationship one forms with their employer. Like the dream HEIs of the AAUP team, the employment and income security reputedly offered by unionized academic tenure (for all upon hire) is not likely to come true for most and is unnecessary in the first place and both unattainable and undesirable in the second, according to PSA.

Concluding Remarks

“Posts are my own views and not those of my employer.”

This disclaimer encapsulates the relationship between HEIs

and their faculty employees, in a model where academic freedom is limited,

integrity is compromised, employment is restricted, and power is distorted. In

the face of obvious value conflicts, obvious absurdities, obvious complicity,

and an obvious alternative, the only reason one would subscribe to the HEI

model is to preserve university and college employers and consolidate power

without or fracture it within the academic profession.

The AAUP team admits it is difficult to hear all the academic voices in the academy. In part, this is due to the static noise of inessential institution-oriented employers, presidents, boards, donors, politicians, investors, and so on. But from the perspective of PSA, the difficulty is more nuanced because our conception of what it means to be an academic is molded by the HEI model. In professions like law and medicine, whether or not a licentiate has ever practiced a day in their lives, they are referred to as attorneys and physicians. It is not clear this can be said of academics.

That said, to what voices is the AAUP team referring? There are the voices of people employed on a permanent basis, a contingent basis, those that were once but are no longer employed by an HEI, and those that stand outside on the street with chopsticks in hand waiting and working for bianzhi (编制). The singularity of the HEI model leaves many academics out of the conversation, while it turns a deaf ear to those that are no longer or who have never been employed by an HEI. These academic voices are also not heard, even by self-appointed advocates of the academic (or is it, faculty?) profession. But whether academics are in or out of the sphere of HEI-cum-AAUP designations, they all find themselves muted by the imperious appeasement of institutions that are themselves subject to the appeasement of Congressional hearings.

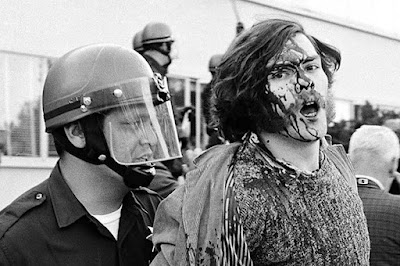

This is not the universitas of which I dream. The PSA model treats all licensed academics equally. Whether you practice or not, as a member of PSA you have a voice as audible and valuable as any other licentiate. The professional academics of PSA have no need of unions that fight on the streets against employers who don police caps and depress the voices of academic and personal freedom. Only the unreflective assumption of universities and colleges could rationalize such twisted stewardship.

As always, I invite contribution to and criticism of the development and promotion of the PSA model.

No comments:

Post a Comment