It’s worth reaching back to the start of this century, to an

exchange between two academics in Canada, to see how meaningful improvement is

not coming to higher education so long as the university and college model remains

unchallenged. I do not mean challenge to some peculiarity of its players, positions,

policies, procedures, processes, or practices, but a winner-takes-all

contest. At any rate, improvement is not coming from academics who fail to see beyond the campuses

they cling to for validation and vacation, memory and mortgage; beyond the

peaks and valleys of unionists, trustees, capitalists, and politicians that

interfere with proper stewardship of higher education.

This must stop. Not by getting your version of your institution in a secure enough position to act as some paradigm for generations to come. It’s by doing exactly the opposite. It’s by recognizing that Oxford, Stanford, Melbourne, McGill, Peking and the rest are the price of an inheritance. They are instruments in a service and stewardship model. They are not higher education. They are not the only means of providing the teaching, researching and community servicing of higher education. They are not many things that they need to be in fulfillment of their social contract, but principally, they are not required.

Stakeholders of every stripe seem determined to overlook these truths and assume their opposite. With awe and assumption, they fight battles within and over institutions that combatants quaintly refer to as their own but which by design, are abstract adversaries in compromising and complex disputes over shared governance, maternity leave, enrolment caps, tuition hikes, civil liberties, parking citations, course syllabi, textbook selections, tenure selections, and so many other (de)selections. Since the higher education institution model entails multiple stakeholders in tension and quarrel with one another over everything from ethos to parking, there is no unified front, with battle lines drawn around idealized versions of aspects of these instruments but never around the entire model itself.

For instance, the best stewardship the American Association

of University Professors has managed for higher education includes decades of

sideline-shouting at university and college employers, a handful of

institutional band-aids elevated to the holy trinity of faculty employment

– tenure,

shared governance and academic freedom – and eventual surrender to the

reality of academic work as unionized stewards bargaining for a (collective) version

of earning and learning as faculty employees of a higher education institution

(HEI).

This waste of precious resources is largely thanks to

the unexamined assumptions and limited imagination of academics, of

which this generation-old academic exchange serves as a typical example.

The People We Call Academics

The AAUP and other guardians of the academe have been

kicking this holy trinity can for a hundred years, up hill. In this exchange, fellow Sisyphians, Hymie

Rubenstein and Lorne Carmichael, are tenured professors. Rubenstein is retired

from the history department at University of Winnipeg, while Carmichael still

slugs it out in the trenches of faculty employment as an economist at Queen’s

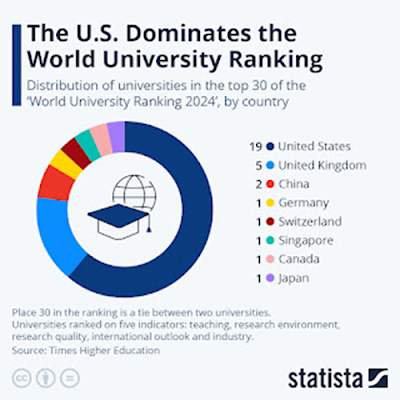

University. Employed by Canadian institutions with middling to mediocre global rankings,

both are examples of individuals (not institutions) whom PSA aims to call to

the academic profession.

In the opening

piece of the exchange, Rubenstein combines principled premises with liberal

use of terms like, ‘empirical’ and ‘data’, while Carmichael responds with

concern over (optimization of) the faculty employment process, as both rely

on sports team and law firm analogies to argue over a place for tenure in the

academe, and parry in the aftermath of a deconstructionist academe that

both consider an embarrassment created and encouraged by the massification of higher

education and faculty employment.

Like Hymie Rubenstein, I

[Carmichael] detest the repressive speech codes of academe, the stultifying

anti-intellectualism of faculty unions and the political mush that

passes for scholarship among so many of my colleagues. I too would like to

see it all disappear.

No matter the source of such sentiment, the implication is a

constriction of the academe that is counterproductive to the work of academics

and so detrimental to the social pillar of higher education. It is a

constriction in (academic) freedom that is a direct consequence of the university

and college model. This is not criticism directed at Deconstructionism, but a

position on its position in the academe, based on a particular understanding of

the ethos of academic work and

conditions of faculty work.

In terms of the latter, tenure distills to earning a living (as an employee of a university or college). It comes down to a job, its security, the conditions, compensation, maintenance, description, evaluation - its hiring and firing. Tenure is logically and logistically tied to assumption of the exclusive conditions of faculty employment for academics who wish to earn a living in higher education, assumption that invites responses like the holy trinity. But this knock-on effect is the end of academic effort to understand and so these faculty employees fail to see that it is the (assumed and unchallenged) hiring and firing that menaces the social pillar and tenure is moot in the absence of this inherited higher education institution employment model.

From tyranny to tenure, our institutional inheritance is the principal author of the problems and solutions that these two employees discuss. In fact, this heritage is assumed in all discourse on all aspects of the social good, from person to parliament, from private to public, and from parking to purpose. All discourse, that is, except for mine. I disclaim the inheritance and wish to contribute to higher education without it, on my own, independent of exclusive faculty employment, because PSA makes this possible and because it is better for all.

Arguing over how best to hire and fire academics in

faculty employment does not produce fundamental fixes but band-aids like the

AAUP’s holy trinity and bargaining units. Fundamentally, the removal of this unnecessary restriction on

earning and learning is a principal purpose of PSA, achieved

in part by licensing academics to

practice higher education as independent professionals, not faculty employees.

PSA does not hire or fire academics to service some institutional employer's

mission statement, crest of arms, Latin moto, board of trustees, careerist president, alumni donors, or anonymous shareholders. Therefore, it does

not require the holy trinity of tenure, academic freedom or shared governance

(of employers) to protect the social good of higher education.

But instead of exploring what naturally flows from

discussion of the legal example, including that is does not require or use the

employment protection of tenure – the very topic of their discussion, hello!? –

Carmichael assumes the inheritance and uses a sports team analogy to elucidate how

(ideally) institutions are to hire the best academic candidate and fire the

worst faculty employee,

In fact, there is an important

difference between a university and a sports team that helps explain the need

for academic tenure. In athletics it is relatively easy to identify the best

young talent. The owners of the team or its managers are experts in the game

and can pick out the best people to hire. In academe this is much more

difficult. The principal of a university might be trained as a historian, the

dean as a mathematician and the associate dean could be an economist. No matter

how smart and dedicated these people are, the state of knowledge is now so

broad and so deep that they would be quite helpless in a discipline outside

their own.

“What to do?”, he immediately asks and answers, “In any good

department it is the incumbent professors who choose whom to hire.” He even

folds in the seven

years of tenure-track employment probation that the AAUP wishes was a

(state, nation, world?) gold standard and these days tries to protect with

strike pay.

Analogy opens the door to alternative answers for what to do,

but Carmichael offers none because he reasons within the assumption of his

inheritance, inside the only higher education model he and his debater have ever known. To these faculty employees, departmental hiring committees, tenure-track

probation and tenure (review) panels seem natural births of the heritage, as I

suppose they are.

But is the Rubenstein-Carmichael exchange about tenure and

its relation to freedoms (of expressing and earning) as an academic or about

the employment of academics as faculty by universities and colleges or is it about

how to protect higher education as determined and delivered by academics in

whatever model facilitates the service and stewardship? In short, is it

possible to have a meaningfully exchange on tenure in the absence of university and college employers?

Rubenstein thinks it’s possible. He points to people like "Da Vinci, Shakespeare, Galileo, Newton, Smith, Mozart, Darwin, Marx, Edison, Freud and Picasso," as evidence that something like “academic freedom is upheld not by the modern tenure system but by hundreds of years of artistic and scientific brilliance rooted in the traditions of Western civilization," rendering the issue of tenure moot. While I sympathize with his scope on freedom, I criticize his failure to include focus on facilitation of its exercise.

Rubenstein speaks of an academic freedom that we all have, or

we might if only we willed and acted on it, each creating our own Sistine

Chapel, cure for AIDS, or monetary theory. But, of course, this brilliant tradition

also includes academics who work in institutions as precarious faculty,

those who do not (now) work for these institutions and those who do not find

themselves in the enviable position of a Da Vinci or a Marx, with benefactors

that put food on the table and clothes on the back in facilitation of the exercise

of Rubenstein-style academic freedom. In this branch of his reasoning, in the

context of the exchange, Rubenstein conspicuously ignores the need for a Medici

Family or a Friedrich Engels and collapses principle into practice, ethos into exercise.

This failure in academic function, pales in comparison to

the folly of these two when parrying over the law firm analogy. As setup,

Carmichael says,

So, you know that if you hire the

best candidates there will come a time when your output will fall below that of

the younger people in your department. In this context, why would you ever

hire someone you expect to be better than yourself? You would just be asking to

be fired.

Descending from his perch atop Western civilization,

Rubenstein introduces the legal service and stewardship analogy saying,

Why would a Wal-Mart recruiter

ever hire someone with good management skills, knowing that he might be

replaced by that person several years down the road? Why do the senior partners

in law firms always try to hire the very best law-school

graduates? The answer in both cases is that poor decisions would soon adversely

affect individual, collective and corporate well-being. Accountability to

superiors—and ultimately to public shareholders—ensures that Wal-Mart

recruiters try to make good personnel decisions; profit-sharing guarantees the

same for law firms. [Emphasis is original.]

Professor Rubenstein’s example of

the law firm is a very good one and illustrates the part of my other argument

that I neglected to explain. He notes that incumbent lawyers are the

ones who judge candidates and yet their firms compete intensively for

the very best young graduates every year. Perfectly correct. But senior partners at

a law firm understand that over time the extra revenue generated by a

smart and ambitious young lawyer will be much greater than her salary. A

good lawyer creates his own job, and continues to do so with every

billable hour.

In academe the athletic metaphor is much more appropriate. It is not that the best athletes do not generate additional revenue at the box office—they do. But the number of positions on the field is fixed. You can only have one shortstop. This fellow could be very knowledgeable about the calibre of the young shortstops available in this year’s draft. But if you ask him to identify the best ones, he isn’t going to do it.

When a university hires a brilliant and ambitious new professor of philosophy, this person does not create the revenue to pay for his position. It has to come from elsewhere in the university’s budget. This is the essential difference between a law firm and a university department, and it explains why, absent tenure, even productive scholars will be reluctant to identify bright new hires. At some point they will be competing for their jobs with the very people they hire. [Emphasis added to indicate seats of assumption and difference between the PSA and the HEI models.]

The ratiocination, the justification, the calculation, the possibility and probability are shaped inside the institutional mold, in an after thought that needs some additional space from the editor. Though entailed by the legal analogy, Carmichael doesn't notice how the solo or partnered practice of law is relevant to tenure (and the rest), focusing only on the law firm associate employee version of earning a living in professional service and stewardship to the social pillar of law. He also fails to notice that the employer is a university, not a limited liability partnership, with each incorporation sporting their own power and ethos peculiarities, including the (relative potential) for ownership of the employer by the employee, as one finds in the case of associates who become law firm partners.

None of this disanalogy seems to dawn on the dynamic duo,

who like the rest of the academe, assume academics will always and only be

institutional employees, that is, unless they manage to make themselves the

employer by opening their own university. Neither Carmichael nor

Rubenstein recognize that in this legal analogy the basic service and

stewardship unit of the PSA model is the professionally licensed, supported,

and disciplined solo practice that is owned and operated by the independent

practitioner.

Even though their disagreement is principally about

(covering the cost of) earning a living in higher education while protecting

and exercising freedoms associated with the work of academics, these tenured

employees of public institutions, whose mortgages are paid for by the state, completely

miss the import of the disanalogy in their own analogy. It dawns on neither to

ask: How do the professions manage to

balance earning a living providing a social good with protecting and

exercising personal and professional freedoms?

Based on significant disanalogy between the institutional inheritance model and both the sports team and law firm models, PSA recommends doing none of the faculty employment, tenure-track, tenure, shared governance, academic freedom, vote and strike stuff because none of it is necessary and much of it leads to absurdity. Instead, arrange for the provision of academic services in the same way that we do medical and legal, or psychiatric, engineering, and accounting services, inside a professional model, not a monolithic McDonald’s model.

If an attorney or barrister in solo practice can attend to

the legal concerns of your family, and the physician or psychiatrist can see to

their health needs, then by analogy I should be enabled to join comparable

professional ranks, hang a shingle for my academic practice, and service your

family's faint or furious curiosity in philosophy for audit or credit toward a

recognized credential - as I did for fifteen years as a faculty employee in the

higher education systems of Canada and China. If I can’t provide the service

you seek, then I’d be happy to recommend a licensed colleague of mine, or you

can look us up in the yellow pages, under P, not F.

But if we can't earn and learn together as we two adults see

fit because an assumed, unnecessary institutional inheritance forms a barrier,

then we

all have a problem. It is a very serious and old problem that academics, as a faculty

employee or not, are to be held principally responsible for creating and

solving.

If you think that this mom-and-pop talk sounds a bit too

ignoble for the noble tower of academic work, just drive

by a faculty picket line. They’re not hard to find any where, any time in

the western hemisphere. Have a look at the noble profession clad in vests of

solidarity orange, waving placards of Starbuck's

stewardship in a model all swallow without awareness of just how bad the

coffee is, because unlike the global beverage franchise, the global university and college franchise has no competitor, no alternative service and stewardship model with

which comparison might finally and properly (in)validate reputed inherited

nobility.

If you find the notion of independent academic practice (in a public system) confusing, think of its seed in the Directed Reading Course, where the professor and the student study together a subject that they choose together, with approval of the institutional employer-enroller and receipt of payment for the course by the registrar.

I took a few of these courses with Dr Peter March and Dr

Robert Ansel, both of whom co-created the professional model now called PSA,

but which was then called, Greenvale. Such education involves me and a

professor studying feminism, as I did with Robert, in working conditions that

are from the faculty employee’s point of view considered extra, unpaid labour

that it does not pay the institutional employer-enroller to promote or permit

because universities and colleges can't manage massification of the education intimacy

found in a Directed Reading Course.

Combined with analysis of the analogy between institutional faculty

employee and individual professional practitioner, this intimacy from the institutional

model offered early instruction in construction of the PSA model. Neither Robert nor myself needed the

institution for our education transaction, but we were forced to use it, just

as when I became his colleague, we were forced to be dues-paying members of the

Saint Mary’s University Faculty Association,

because we were employees of the institution, because this is the only way that

we can earn and learn in higher education.

Peter and Robert were Associate Professors of philosophy, one with an Oxford doctorate and the other with a Cambridge. One wrote a dissertation with two references (John Lock and Albert Einstein) and the other a 600-pager on the conditional in formal logic (the concept of “if,” if you will). According to Carmichael, these academics employed as faculty fail to generate revenue sufficient to cover the institutional cost of their employment, which is unlike an attorney employed as an associate at a law firm who bills better hours over time to pay for their position and generate profit for a firm that one day this employee might own in partnership.

Having been married to an attorney for many years and a

faculty employee for many years, I know both sides of this analogy quite well -

especially considering the happy coincidence that the PSA model was created

during the overlap of these many years. The thing is, as is true for all arguments

from analogy, they break down in disanalogy and while Rubenstein and Carmichael

were having this exchange at the turn of the century, I was a decade ahead of

them in a (lived) analysis of the law firm analogy that they fumble.

I quote Carmichael at length because the text illustrates

the dereliction of academic duty found throughout the academe, but also because

his budgetary claim regrading the (sustainable) employment of philosophers can

be massaged into a criticism of PSA claims regarding funding, like that the

total cost of higher education provision in a professional model can be reduced

by at least 50%. [For finance arguments see: Canada, Australia, United States.]

The Cost of (Academic) Freedom

Quickly jumping through Carmichael’s reasoning, landing on

relevant assumptions, we get: Higher education is a public good and a

university degree (education?) should (must?) include some study of philosophy

(for instance); but providing a university education in physics, medicine, or

computer science is budget hungry, demanding much of the teaching budget of the

institution, with not enough left to cover the cost of employing (tenured?)

faculty in the philosophy department.

Having made these budgetary claims, as though they were

obvious truths not in need of specification by analysis of empirical data, and

himself earning as a tenured employee in a higher education job market shaped by

assumption of exclusive institutional employment, this Professor of Economics

concludes, "the new professor of philosophy, this person does not

create the revenue to pay for his position" and so we need tenure.

Extrapolating from faculty philosopher to professional

philosopher, the criticism goes: In arguing for the financial (and economic)

superiority of the professional model over the institutional model, the tendered

calculations are too imprecise, failing to capture the funding and budgeting realities

of institutions that (must?) employ faculty like philosophers at a loss. In its

crude calculations, PSA uses faculty and student full-time equivalent and headcounts

to project independent solo practice revenue and income based on typical

sources of university revenue and expense, but such calculations are not

weighted for discrepancies in the financial sustainability of some faculty

employees. This table for Canada represents what the criticism identifies

as typical miscalculations.

PSA responds with logic and numbers.

Numerically, this table represents the total and partial use

of one category of institution revenue: tuition, fees and aid. With this in

mind, we are closer to the reality of PSA finance calculations and claims, and

at a juncture where proper expertise is needed, perhaps from a Professor of

Economics who claims the financial realities of the inheritance he assumes (unfortunately)

require tenure to protect his position among the very best.

I'm someone with experience and reason that tells me academics

in fields like philosophy, history, business, law, sociology, economics, psychology,

and others can operate solo higher education practices on the revenue from

Student Aid (E) alone or just the Tuition and Fees (B), if academics earned as

practice revenue (some portion of) the full-time equivalent portion of the tuition,

fees and aid revenue that unnecessary, interfering middlemen traditionally receive

and then budget for faculty employee compensation in a model that includes said

faculty employees (ideally) sharing in the governance of said allocations to

themselves from said employer in a twisted mess called a university.

Recognizing that PSA offers a universitas without

these institutional twists and that we are talking about the provision and

protection of a social good, do you think the tally of full-time equivalent and

headcounts for academic service and stewardship would go up or down in a professional

model? Would access on every measure that matters be expanded or contracted if

individuals (not institutions) were licensed to provide higher education? Have

such numerical questions ever entered your mind (when throwing around an analogy

from the professions)?

Logically, the institutional pooling, budgeting and

distributing of funding for higher education (from all revenue sources) entail

assumptions and implications that must be considered in comparison to the PSA alternative.

To start, there is the assumption that higher education institutions are the

best (funding) arrangement for the social good. Certainly, they are the only

arrangement on the planet. But this implies that any relative claim like being

the best at service and stewardship is nonsensical public relations, made

sensical only by something like PSA that challenges the boast.

Another assumption is the prioritization of institutions over individuals, of collective benefit over personal benefit from earning and learning in higher education. I can't tell if the assumption is open or hidden, but PSA makes it unnecessary, as it exposes the university and college failure to massify the Directed Reading Course (for instance).

Suppose some citizens don't give a shit about (a degree in) Physics and Biology or Canadian Studies and Puppet Arts but want to study the philosophy of caring about such subjects (in solidarity) with others who disclaim the institutional inheritance. In such a case, tax dollars are not being spent on education that citizens think worthy of the public and private (opportunity) costs associated with choosing to earn or learn in higher education.

With PSA, we are enabled to study what we want with whom we want in ways we want on a scale of access and intimacy that cannot be matched in the institutional model. In development of ourselves as persons (and citizens) we should be enabled to use our (higher education) tax dollars as we see fit and certainly not in the form of more student loans used to pay the high tuition and fees of an assumption.

Of course, there is more to say, and it has been said over

the past thirty years and throughout this blog during the past thirteen. Admittedly,

even with it said, the logic and numbers might still fail. The thing is, how do

you know and professionally, as academics, shouldn't you know? For instance, isn’t

this knowledge relevant to (the resources spent on) the question of the

necessity of tenure to the provision of proper higher education?

Carmichael claims that promising philosophers don't generate

revenue sufficient to pay for their position in the university, but then how

are they paid? How can universities and colleges afford faculty freeloaders

like philosophers? Does the revenue to cover the cost of their employment come

from profits generated in the chemistry or computing science programs? Is the

expense covered with university bond sales, interest from the institution investment portfolios, its patent monetization, its lobbying efforts, or a

billionaire's endowment for the study of philosophy?

The largest expense of most organizations is the cost of labour

and so its reduction is an obvious solution to insufficient or precarious (institutional)

funding and revenue. So, predictably, university and college employers hire and

fire part time, adjunct, casual, precarious (philosophy) faculty and pay them

shit to reduce institutional overhead. I suppose the philanthropic philosophic billionaire

would be impressed.

But is Carmichael referring to the cost of covering this

bargain basement faculty majority or the minority tenure-track and tenure

types, whose annual higher education earnings range from $80,000 to $120,000? Bringing

the logic and numbers together, we can suppose he assumes an ideal system where

all the faculty enjoy tenure-track or tenure employment status (possibly backed

by contract labour law a la Rubenstein), with sustainable, secure, sufficient

funding or revenue, requiring little to no labour cost-saving measures, and

offering at least the current level of income, accessibility and quality.

In stark contrast, this is how PSA suggests covering the cost

of academic service and stewardship (in philosophy to society). For academics to

gainfully contribute to higher education they need only the price (or tuition) of the

courses they develop and deliver. For instance, if I charge $500 per full-credit

course and service 200 students in the year, then my independent professional

academic practice generates $100,000 in gross revenue from the tuition revenue stream,

alone.

For comparison, in the United States, the 2024-25 rounded average

advertised annual tuition and fees for a four-year undergraduate degree is

$11,000 (public) and $43,000 (private). If a full-time student typically enrols

in the equivalent of five full-credit courses per annum, then from the point of

view of the citizen-student, they pay $2,200 per course in tuition and fees. The

same can be done with credit hours, but I'm old school.

This crude calculation suggests that for less than a quarter of this average advertised revenue source, people-citizen-students can earn a degree in the Humanities, with a major in philosophy, from people-citizen-academics who legally and gainfully contribute to higher education as philosophers. So, what exactly does Carmichael mean when he says philosophers don't cover the cost of their employment? Is he claiming that what the philosopher generates in revenue for their employer is less even than this, less than one-quarter of the current tuition and fees? And with less fiscal and greater philosophical import, does it even make sense in the public system to speak in this way, in the way a capitalist company talks of ARR and RPE?

If the full-credit course was only ten percent of the 2024-25

advertised price tag, then with 200 course purchases, this generates $44,000 in

revenue for my independent solo academic practice, which in Asia, South America,

and many parts of North America and Europe is sufficient to live and contribute

as one sees fit in a professional higher education model. Further, this financial

reality says nothing of the other common institutional revenue sources that

apply in a wholesale model like PSA, nor anything of the tax-breaks, low

interest business loans and other government programs and policies that can

support professional academic practice in the community. As part of my

experience that tells me this can and should be done, I owned an education business

that earned me an early retirement through contributing to the spread of critical

thinking – a staple of philosophy department feeder courses in universities and

colleges of the inheritance. Sure, this was a private venture, but come on, use

some imagination – that’s what you’re paid for.

Consider again if some citizen-student complains, "I

don't want my tax dollars going to fund Astrobiology or Philosophy. I want (my

kid) to be an accountant." Paraphrasing Carmichael, the inherited response

is, “Too bad. That's what it cost to operate universities and colleges, where the credentials come from, and

these institutions are flat out the best or the best we can do for higher

education. Inside this exclusive institutional funding, employment and education

arrangement for service and stewardship, when a university hires a

brilliant and ambitious new professor of philosophy, this person does not

create the revenue to pay for his position, but higher education should (must?)

include philosophy.”

Maybe Carmichael is correct, but this has little to do with service

and stewardship offered from within a different model. The pooling, budgeting

and distributing of higher education funding and revenue from all sources is

different in PSA than in the institutions of the inheritance, where maybe

philosophers are faculty freeloaders. But in PSA, for around half the current

tuition and fees alone, philosophers, sociologists, historians, economists, and

so on, can gross $200,000 per year in working conditions determined by

independent professional prerogative, not some exploitive institutional

employer over which employees ideally share governance but not ownership and a

three-year contract that is two years late for a position that (apparently) everyone

in the academe knows doesn’t pull its (corporate) weight.

This is a quick shuffle and deal of my financial argument

for PSA, which is part of the economic argument for PSA. In this light,

Carmichael's claim that philosophers are a burden on institutional budgeting

might be true, but that does not mean philosophers are a burden on higher

education, because in the end, it might mean that universities and colleges are

the real burden.

All the pieces are there for an academe of Rubensteins and Carmichaels to put together during prolific professing sessions. These two discuss the social good of law and how the social contract for its service and stewardship is a professional one, but like the rest of the academe they cannot see past their collective assumptions to properly analyze the implications of the analogy they ironically introduce for clarity on an unnecessary employment term of an unnecessary employment model. This academic failure leads to the failure to recognize that in the legal profession (and professions in general) there is no tenure and the basic service and stewardship unit is the solo practice so that if indeed higher education were offered in an analogous fashion to that of law, then their exchange would be made moot – not to mention much of the work at organizations like the American Association of University Professors.

The cost of this menacing mass assumption to people and civilization

is extraordinary, while faculty bounce around without comparative reference declaring

how the institutional employer is the very best we can hope for in service and

stewardship. On any measure, PSA offers cost reduction that universities and

colleges can not hope to, as they constantly cry a chorus of poor. All of this is

open to the mind that explores it, and the academic mind is charged with exploring.

Conclusion

Once again, tenure is a hot topic thanks, once again, to the academe being supercharged with politics. PSA recognizes that there is no separation of state and school, like there is with state and church, and so the model attempts to reduce undue influence and interference from the state and its institutional instruments of higher education, mitigation well beyond what a band-aid like the holy trinity can ever hope to offer individuals or society. Carmichael and the gang think that tenue is the answer, because they assume that a university employer is the only answer to how we could and should provide and protect the social good. Rubenstein and the gang think a (union-backed) employment contract is the best answer to the question of how to steward the service of higher education from within the inheritance that I disclaim.

PSA rids higher education of the exclusive employment of academics by institutional employers and allows people-citizen-academics the same sort of personal and professional freedom that attorneys enjoy in the social pillar of law or physicians enjoy in medicine. In contrast, Carmichael asks for space to complete his analysis of the law firm analogy and Rubenstein steps over the practical need for a Medici or Engels in the principled exercise of (intellectual) freedom. Marx writes nothing without a meatloaf and the more secure is the loaf the more secure is the (exercise of intellectual) freedom.

It’s true, I don’t want to live in Communist China as an academic – I tried it. There is no academic freedom in the state-run higher education system of the Chinese Communist Party. As demonstration, compare the work and commentary on (global) economics coming from Chinese citizens who are faculty at Peking University versus the same coming from their colleague, Spanish-born, American citizen, Professor of Finance, at Guanghua School of Management, Michael Pettis. You will quickly learn there is no academic freedom in China. And Pettis is not to be used as proof of the opposite.

Politics affect freedom, earning and education, but the

who and how of the loaf on the table is what ultimately dictates sustainable exercise

of one’s will. At the same time, education is a collective activity, an

exchange of wills, with the fundamental unit in the exchange being the teacher

and the student, the master and the scholar. After the loaf, the lecturer and the learner, the rest is apparatus.

PSA underwrites this basic facilitation and education unit with the professional solo academic practice of higher education, as the social contracts for law and medicine are struck using the professional model of service and stewardship. I might need a bench upon which to profess, but I do not need the property of a university or college, used as an employee who has no hope of ever owning the bench, in an exclusive employment arrangement where there is a pretty good chance of calling a park bench my office.

Tenure is moot in the professions. Tenure only has life in

the inheritance. The inheritance can be (and should be) disclaimed. The

inheritance can be (and should be) replaced with a professional model (like

PSA). There is much more to say that glues these claims together and it has been said

on this blog and here on the topic of tenure.

If you have something to say, I’d like to hear it. I sometimes think, even now after all these years of considering the question of PSA, I must be mistaken because the silence is deafening. If so, please just say how it is that I am mistaken, and higher education cannot and should not be offered in a professional model. The door is always open, and the model is free for the taking.

No comments:

Post a Comment